Parade (a Drip, a Drop, the End of the Tale) [solo]

Japan House São Paulo, São Paulo

Aug. 30–Nov. 21, 2021

Curation: Natasha Barzaghi Geenen

Venue: Japan House São Paulo

photo: Japan House São Paulo/Marina Melchers

Q & A for “Parade (a Drip, a Drop, the End of the Tale)”

I have learned from the press release that the exhibition is the homage to Antonio Carlos Jobim and you use also objects evoking his famous Águas de Março in your installation. Could you share your feelings or thought about him, how you knew him?

Yuko Mohri: I don’t remember when I have heard Águas de Março for the first time, as it is so famous standard of Bossa Nova. I should have heard it somewhere else. I think it was a duet with Elis Regina, which is the version I love the most up to now.

This is what I have learned recently, the original version of Águas de Março (Disco de Bolso/1972) is so up-tempo and almost punkish. Jobim sings, keeps playing guitar and fade out at the end of the music. The entire arrangement of this suggests a perpetual motion. The sense of perpetual motion is common to my kinetic sculpture Parade.

I always thought the lyrics depicted in Águas de Março totally fits to my perspective I pursuit.

In his lyrical world, objects are lined up, they are related to natural events (movements) and finally, the song releases the feelings and sensations of people who see these sceneries. I feel his music describes “The poetry of beings and things” I aim for, or some new sense of ecology. This time, my installation includes an object which has water dripping, so I cited a reminiscent part of his lyrics for the subtitle of my work.

I would say that the exhibition is not really a homage but rather inspired by a great Jobim.

By the way, I have known from his sister Elena’s memoirs, that Águas de Março was conceived at the moment when he went through a dark tunnel, at the end of a long depressive period he experienced, after his immense success with Girl from Ipanema.

Actually we feel a premonition of light toward the end of the music.

Even though we are under the disaster of COVID-19, the end of the tale is coming someday. The lyric of Águas de Março ends with this phrase—The waters of March, it’s the end of all strain, it’s the joy in your heart.

I have heard also that Parade is named from a piece by Eric Satie for ballet, and influenced by his concept of “Furniture music.” Do you often inspired by music?

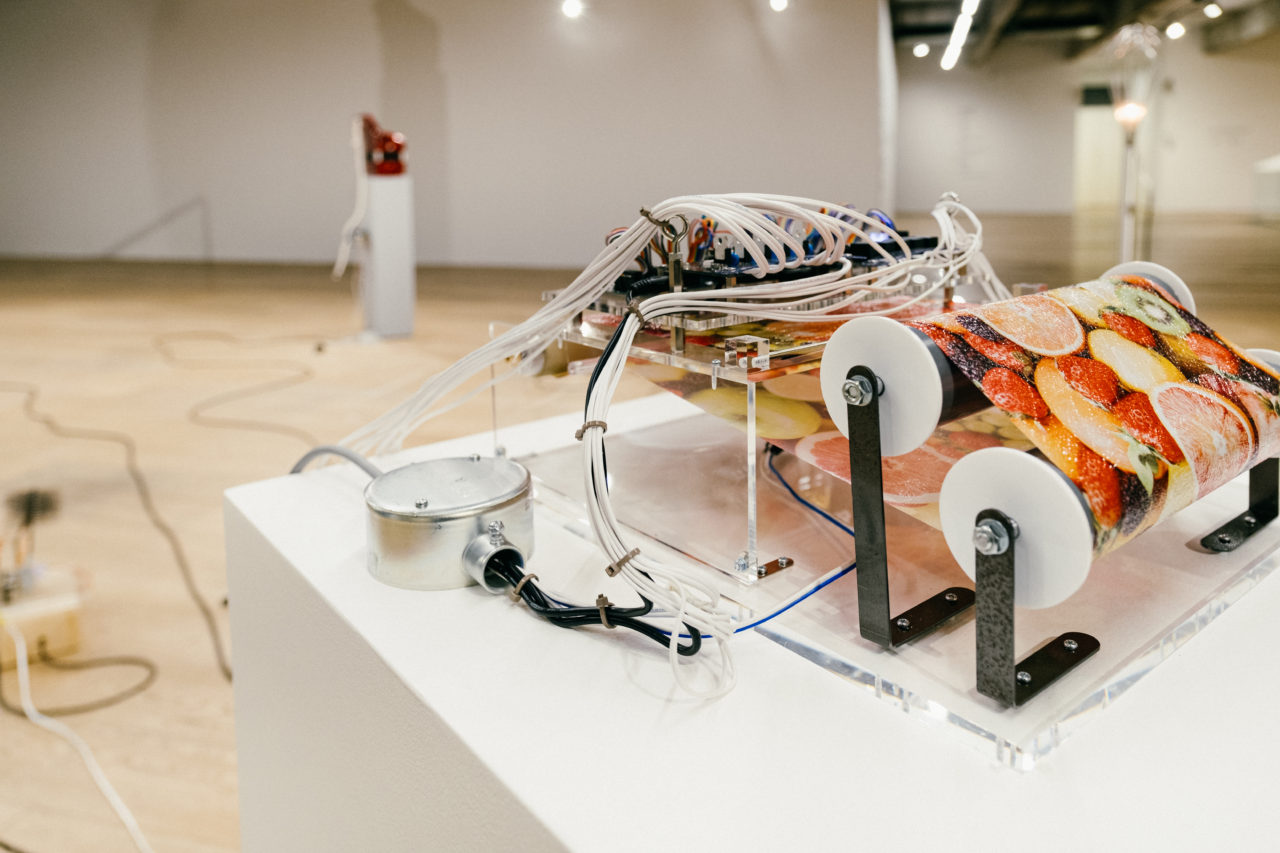

Yuko Mohri: The Parade originally picks its theme from the “Furniture music (Musique d’ameublement)” composed by Eric Satie, which is often called as a founding of ambient music. As the first movement of this piece is titled “Tenture de cabinet prefectoral (Wall Paper in a chief-officer’s office),” I thought of a system that the instruments play a music automatically through a sensor reading motifs of scrolling wall paper, and turning on/off the power. This time, I used a table cloth with fruits motifs, not a wall paper.

I have also learned from Jobim’s sister’s memoirs mentioned above, that the idea of Águas de Março came to mind of Jobim, when his villa was in construction at Poço Fundo. So, accidentally, I share the theme related to “home” with Jobim.

Anyway, Satie is always important artist to me. My first piece, in my early twenties, was inspired by his Vexation, which takes almost one day (18–25 hours) to play. I created my first piece, through adding elements of “error/accident” to Satie’sVexation. Eric Satie, Marcel Duchamp, John Cage . . . . I respect all these artists who had lived a difficult time, in a nonchalant way, without falling into an easy humanism. They didn’t ignore or simplify the complex events such as error/coincidences/portents/silence, on the contrary, they sublimed these elements into artworks, through their soft and flexible sensitivities. Their ability to accept such complex elements as they are, the humor we can see in their works, the attitude of them who followed a “Life through inadvertence” (as said strict Pierre Boulez) looks to me, if I can say, like a rich and tasteful unfiltered wine, and I always refer to them, their spirit.

As to music, when I was a high school student in Tokyo in 90’s, every sound sources once released in a form of black disk were remastered in CD―digitalized―and lined up on the shelves of record shops. Although such phenomena is so called “post-modernistic consumer society,” but to me, young, such period was rich of diversity, like Cambrian time when the livings were explosively increased. People loving music in that time should have felt released from a framework of genre, by discovering various music and sounds which were dispersed, even buried, all over the world. (Some people lived in these time should still have such feelings.) Of course, many Brazilian music were found among them. In addition to Tom Jobim and João Gilberto, who were originators, I started to listen to Caetano Velozo, and artists of Tropicália movement, such as Tom Ze or Os Mutantes. Arto Lindsay (and his band DNA), who produces many Brazilian artists, was also one of my heroes, in my high school days.

The attitude of these musicians, a sense of freedom I felt from the music, always influences me, and I think its importance is immeasurable.

photo: Japan House São Paulo/Marina Melchers

EXPOSIÇÃO // PARADE – UM PINGO PINGANDO, UMA CONTA, UM CONTO

CONVERSA COM A ARTISTA YUKO MOHRI

ADRIANA E ALBERTO TUFAILE FALAM SOBRE 'PARADE - UM PINGO PINGANDO, UMA CONTA, UM CONTO'

O MÚSICO DANIEL DAIBEM FALA SOBRE 'PARADE - UM PINGO PINGANDO, UMA CONTA, UM CONTO'