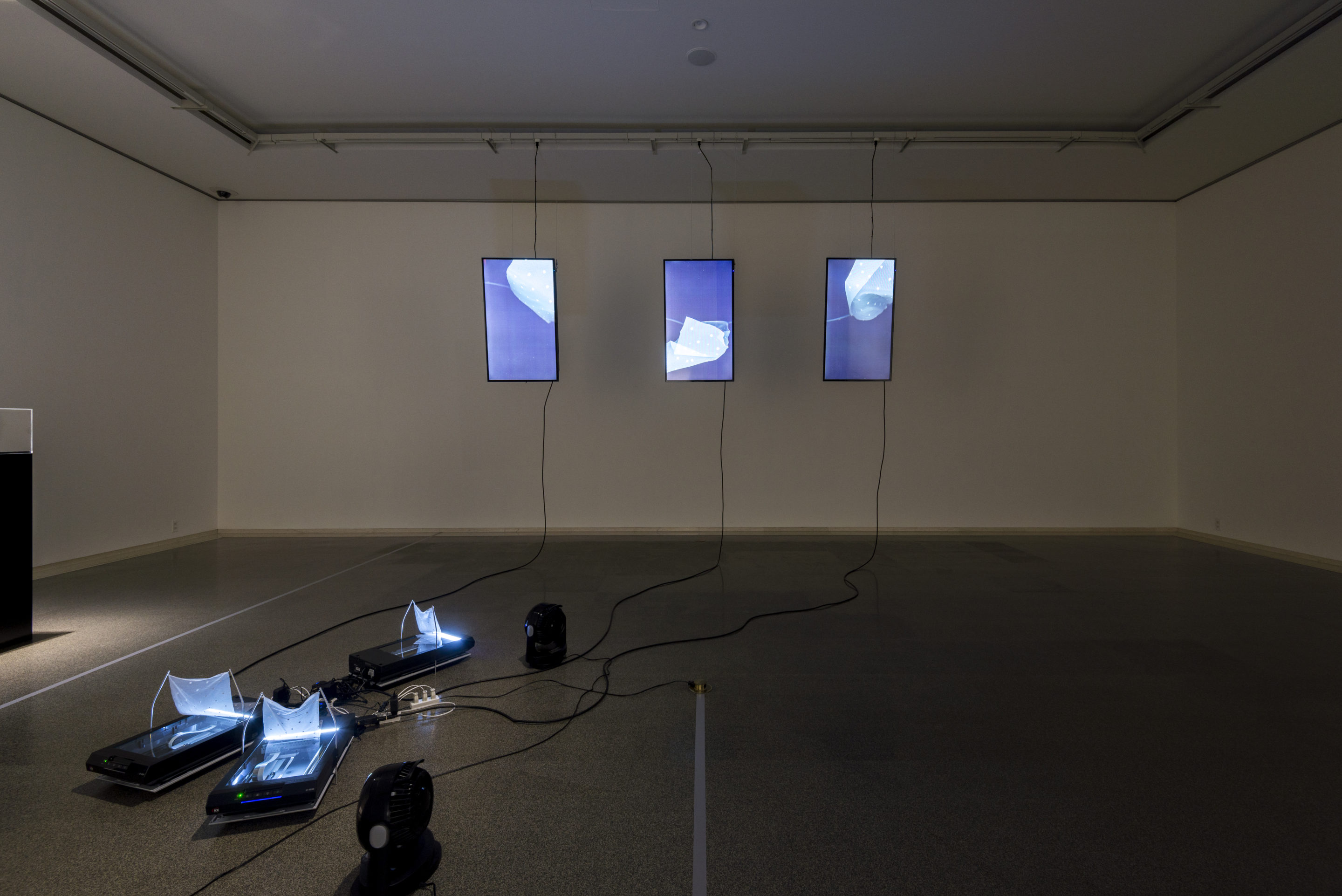

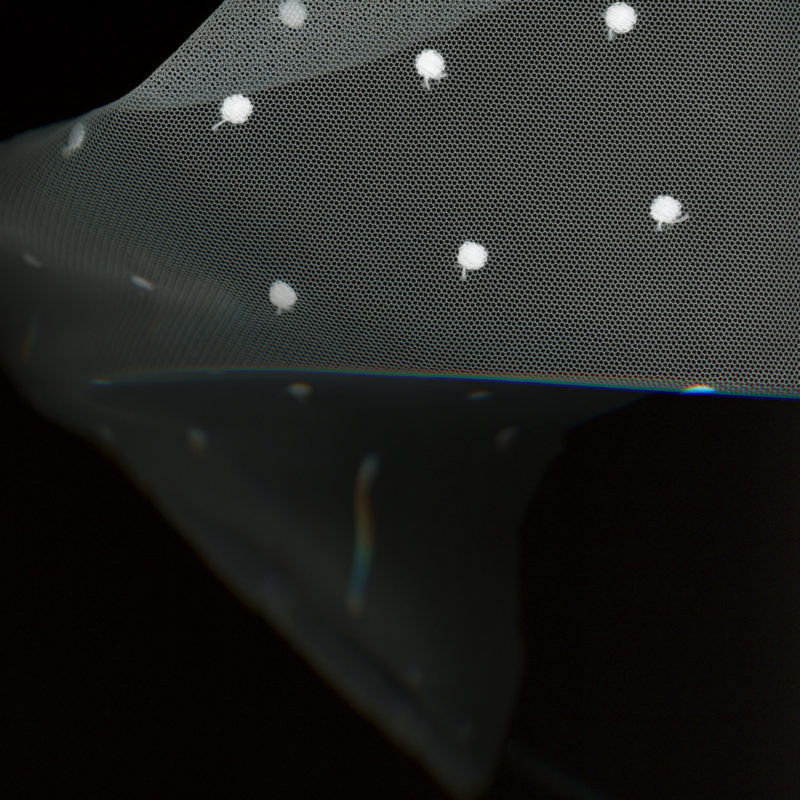

The Flipping-apparatus, Three Veils

2018

Photo: Yuki Moriya, National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

This is a re-interpretation of The Large Glass by Yuko Mohri, whose works are sensing invisible and intangible powers, through using errors of machines or chance factors hidden in the natural phenomenon. Mohri, applying various apparatus and optical medias, tries to construe, in her critical view point, an “electrical undressing” lead by a “circulation of sexual desire,” that Marcel Duchamps has certainly intended to depict in his The Large Glass.

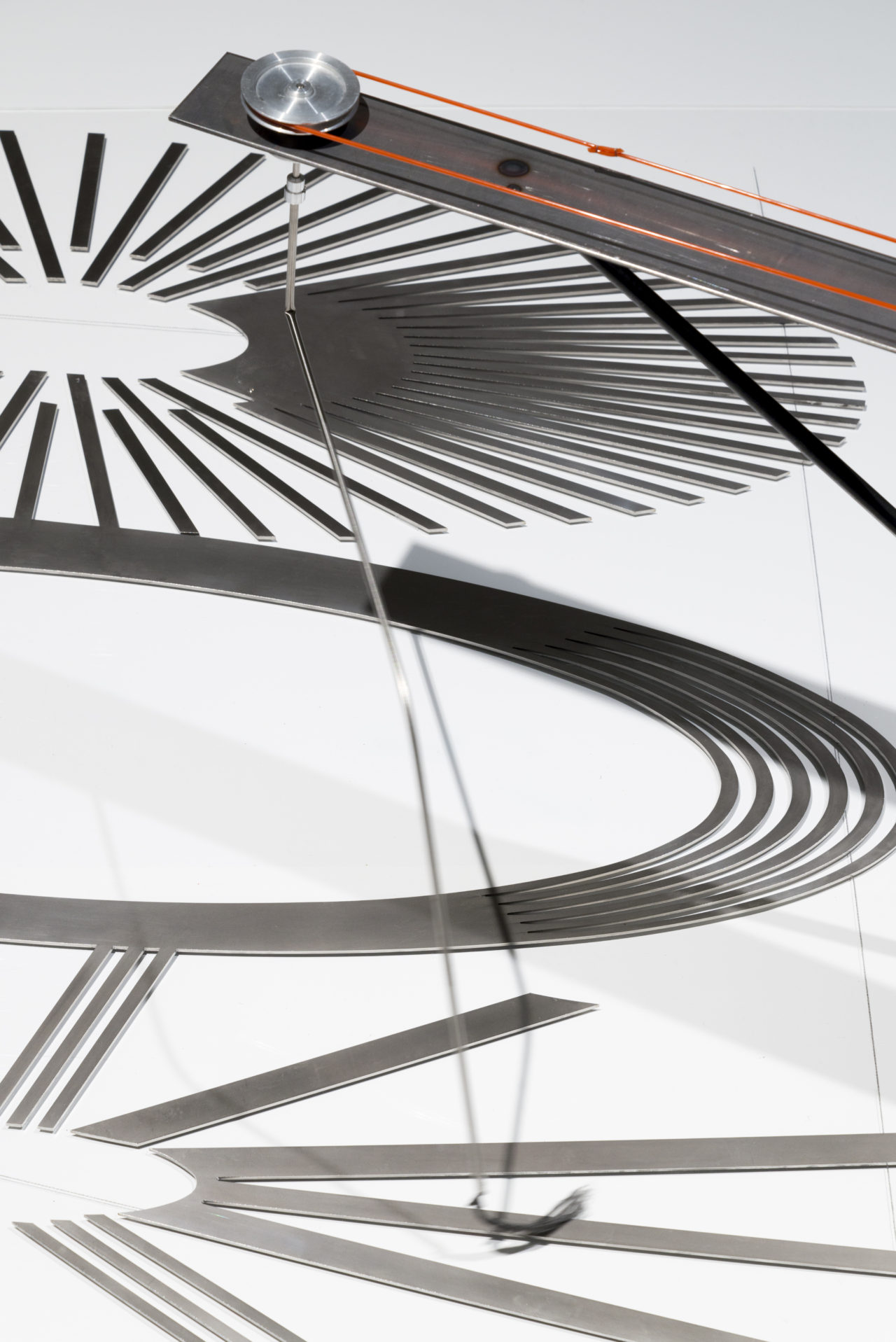

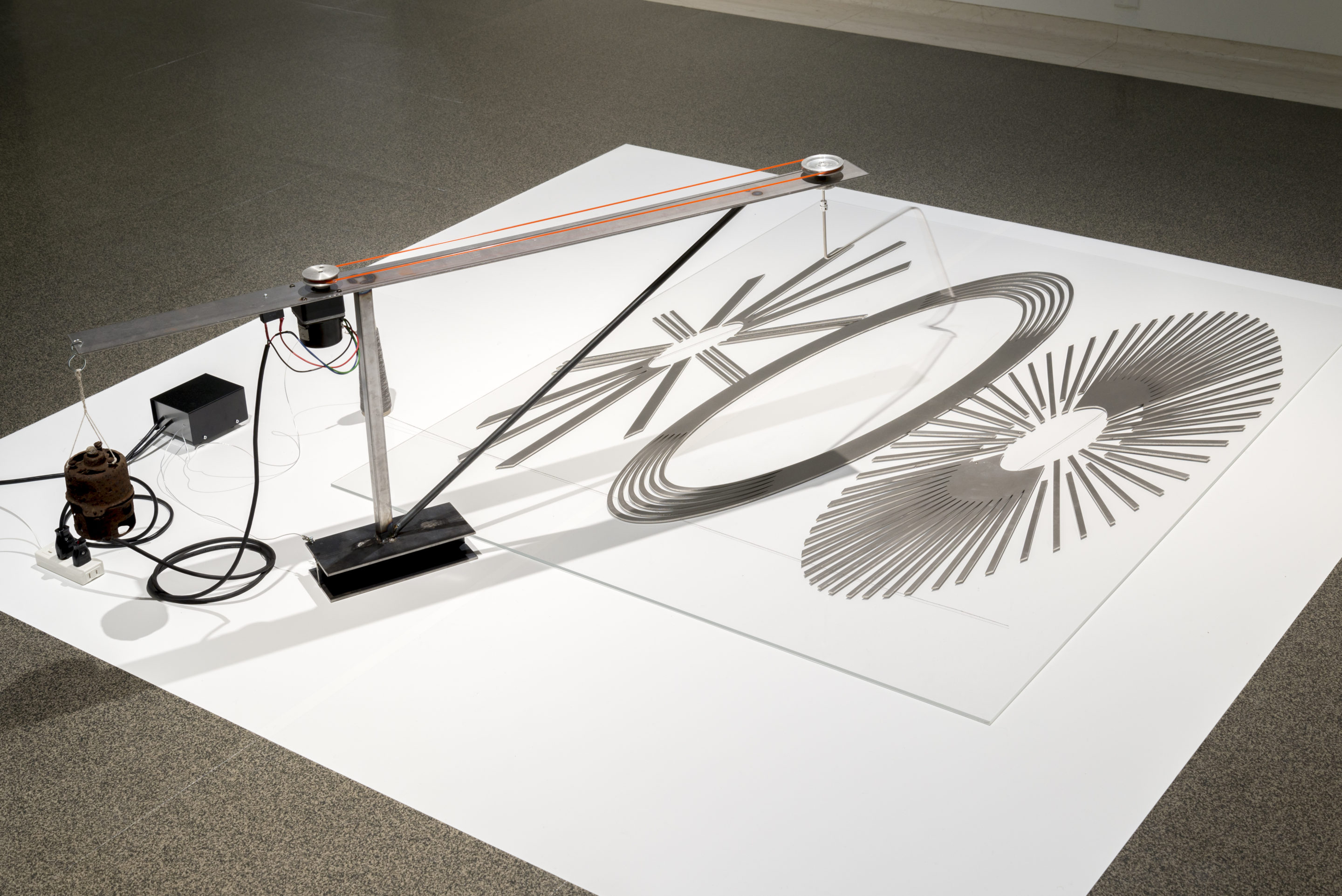

When an electrical conductive yarn rotating by a motor touches on slightly electrified and stainless-made “Oculist Witnesses,” a fan, placed beyond a partition, will also be electrified. Then, wind generates and three veils of “The Bride” gently sways. These three veils are set up on scanners programmed to work at intervals so that their moves are regularly recorded. The scanned images, being reduced to the three primary colors, are projected on three monitors placed as a position of “Draft Piston” of The Large Glass.

It is said that Duchamp introduced a chance factor through a design of “Draft Piston.” “Duchamp, hangs down a rectangle gauze in front of an opened window, and photographed the shape of it three times. The gauze shows in each time different distortions, depending on ‘whether it is accepted or refused by the wind.’ The forms of distortions, recorded by a camera, are served as a basis of irregular shapes of ‘Draft Piston.’ It can also be regarded as an example of a chance or a nature power used for the art.” (Calvin Tomkins, Marcel Duchamp).

Mohri, inheriting the chance factor concept from the work, replaced these three photographs took by Duchamp with a series of images, “irregular shapes,” which could have infinitely been generated by scanners.

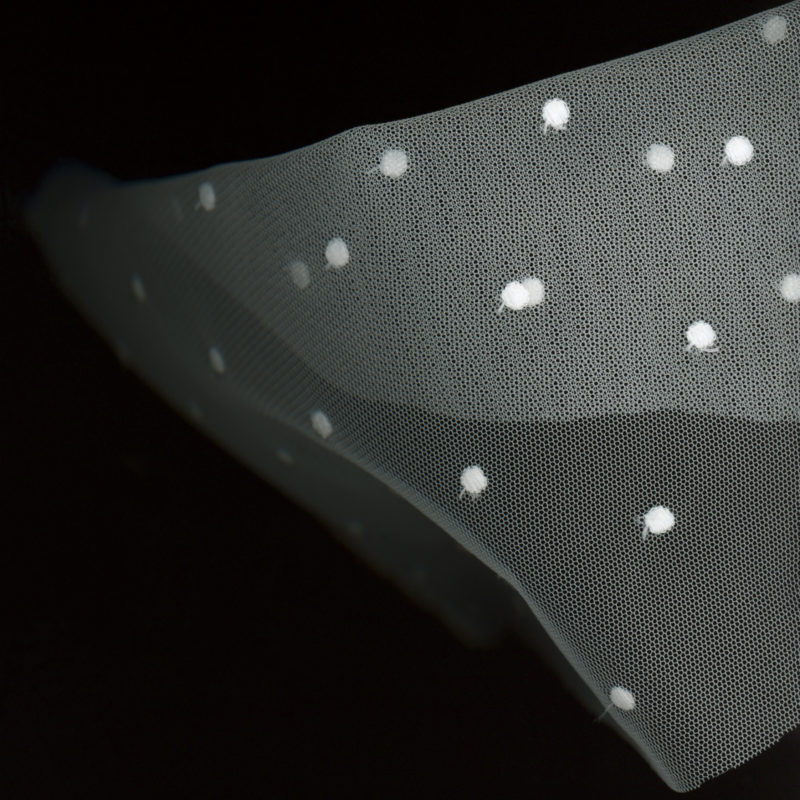

Photo: Yuki Moriya, National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

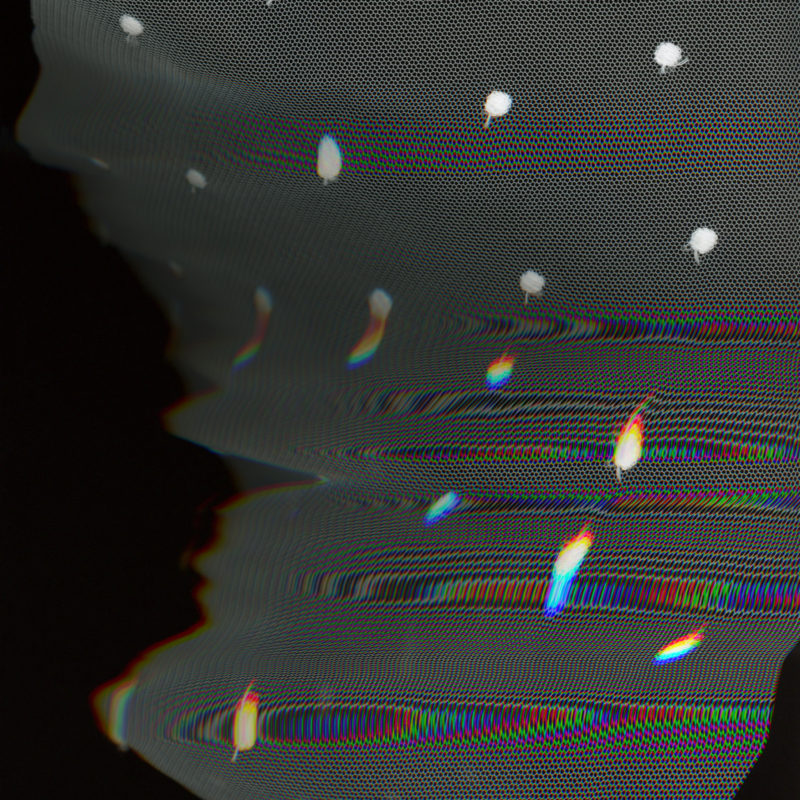

Photo: Yuki Moriya, National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

This Peace was exhibited with Duchamp’s three ready-mades and Boîte-en-valise, special edition for Maria Martins. Photo: Yuki Moriya, National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

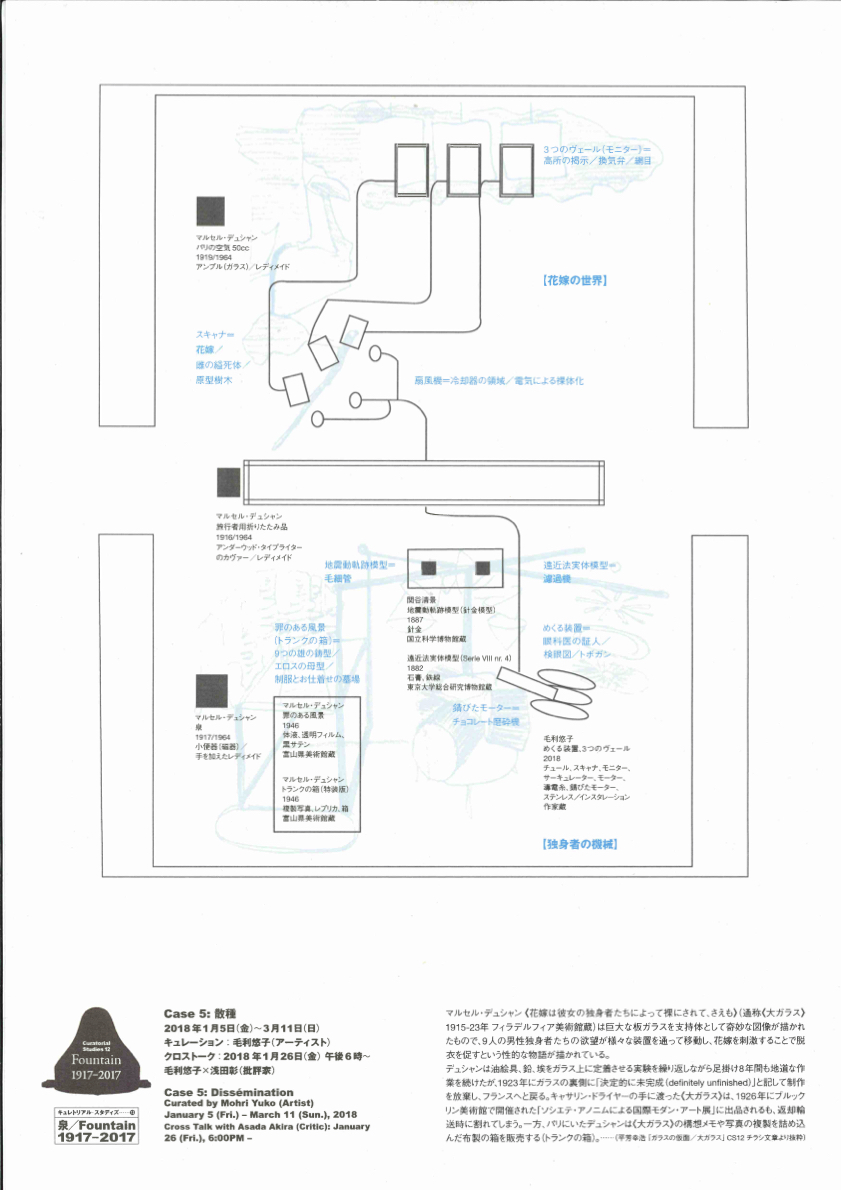

Note about Dissémination (Dec. 8, 2017)

Duchamp was working on his readymades at the same time as The Large Glass. This exhibit focuses on whether or not there is some connection between the two.

Some hints are contained within the works themselves. Next to a miniature (!) of The Large Glass, the main component in Duchamp’s portable work Boîte-en-valise (Box in a Suitcase), there are miniatures of three readymades arranged from top to bottom as follows: 50cc of Paris Air, Traveler’s Folding Item, and Fountain. According to one theory, these were intended to correspond to the three parts of The Large Glass: the bride section at the top, the border between the upper and lower parts (a wedding dress or clothing — something that can both taken off prior to “the act” and put on after “the business” over? LOL), and the bachelor section at the bottom. In a large-scale retrospective held at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1963, the curator, Walter Hopps, made a cute display with the three readymades arranged vertically as a reference to Boîte-en-valise.

* * *

It is widely known that Duchamp hung the readymades around his studio. And some have suggested that he did this to understand the relationship between two and three dimensions — i.e., the relationship between the shadows of the hanging objects and the walls and ceiling on which they were projected. In other words, the shadows were two-dimensional projections of three-dimensional objects. Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” is an idealistic anecdote, and Duchamp came up with the idea that the three dimensional world we live in is actually a projection of the fourth dimension.

* * *

In graduate school, whenever I had time on my hands, I would wander around and eventually end at some kind of museum. I’ll never forget what a mind-blowing experience it was to encounter Model of Seismic Vibration Traces on one of those trips. The model, based on an earthquake that occurred on January 15, 1887, used bent wire to show how a certain point on the ground changed according to the vibrations at any given time — in other words, it was a projection of the fourth-dimensional world (time) on the third-dimensional world. Since the device was made in the late 19th century, it was made by hand instead of with a precision measuring instrument or a computer, and the amount of information it contained was truly stunning. The rough handmade quality also gave it a humorous appearance.

Another thing I saw on a graduate school-era walk was a Perspective Entity Model. This complicated contraption was a three-dimensional model of a three-dimensional spatial concept expressed in the two dimensions. There was also something funny about the deadly serious air of the device. This is slightly off topic, but the artist Jiro Takamatsu was also attracted to this sort of thing, as seen in a work like Chairs and the Table in Perspective.

Since the majority of Duchamp’s unpublished notes in A l’infinitif (The White Box) have to do with the fourth dimension and perspective, I thought these devices would be appropriate for this exhibit.

* * *

This might sound presumptuous, but based on my intuition as someone possibly in the same line of work as Duchamp, it is hard to imagine that there isn’t some sort of connection between the ready-mades and The Large Glass. Isn’t that what he’s hinting at in Boîte-en-valise? Assuming that this is the case, I decided to copy Boîte-en-valise and the Pasadena show, and shove (this reproduction of) Duchamp’s work Fountain, which has been subjected to all sorts of things during this series celebrating its 100th anniversary, up against The Large Glass.

My methodology was the exact opposite of Duchamp’s. I turned The Large Glass, by definition a two-dimensional work, into something three-dimensional, enabling the viewer to walk around it as they look at the piece. In other words, you the viewer are already inside The Large Glass. The awareness or experience of walking around the work, which has a certain degree of thickness (or in this case, height), might be seen in contemporary terms as akin to the relationship between a planar map and a global navigation system (discussing this concept with Sekai Kozuma proved to be very helpful). If you can forgive me for focusing on the unpleasant nature of the subject matter, the framework makes for a truly splendid Large Glass. Alongside it, I have arranged the readymades in tribute to Pasadena, making the space a virtual reproduction of Boîte-en-valise.

This thick two-dimensional object (=three dimensional) functions as a projection of the fourth dimension. Doesn’t this make the relationship between the third and the fourth dimensions somehow plausible?

* * *

The exhibit also encompasses some gender-related elements, but since I have already gone way over my word limit here, I will leave you to your own devices. One thing you can say for sure is that even though all of us artists are Duchamp’s (unfertilized) children, regardless of a few queer elements, the boyish artist doesn’t seem to have had any egg elements.

Yuko Mohri Dec. 8, 2017

Photo: Yuki Moriya, National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto